Modeling as a Prescription for Efficient Health Care Redesign

Health care reform is here, and many hospitals and health systems must become more efficient to remain viable. A number of factors are playing a critical role in determining which health care providers are staying ahead of the rising bar; such as efficient space design and space reuse, cost-effective management of staff, careful adoption of new technology, and lean management practices. Knowing the current baseline of operations and knowing how these factors influence each other, health system planners can put sophisticated modeling solutions to work to determine which potential efficiency improvements will result in the most savings over the long run.

Health care reform is here, and many hospitals and health systems must become more efficient to remain viable. A number of factors are playing a critical role in determining which health care providers are staying ahead of the rising bar; such as efficient space design and space reuse, cost-effective management of staff, careful adoption of new technology, and lean management practices. Knowing the current baseline of operations and knowing how these factors influence each other, health system planners can put sophisticated modeling solutions to work to determine which potential efficiency improvements will result in the most savings over the long run.

Modeling Approaches

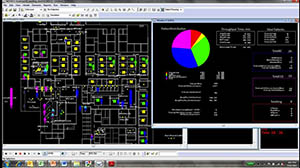

Two modeling methodologies promise to help planners visualize the results of their design and policy decisions. Computer simulation modeling can accept any combination of space, process, staff and patient volume to show how modeled changes will impact day-to-day operations, resource capacity, physical space and patient throughput.

To determine how reliably a modeling solution can predict an outcome, it’s helpful to verify the baseline model, which is a reflection of actual operations. The first step is to identify measurable goals to test against. These typically include such factors as patient length of stay and staff coverage hours per visit.

A second methodology is the use of interactive, customizable dashboard products to manipulate variables in a way that is easy to understand, provides clarity and produces results on the fly. If the model is built right, a dashboard solution can answer questions just like a data-mining tool.

Challenges to Planners

Health care reform demands that a health care provider consider shifting spaces that were traditionally used for one function to a different function for better cost containment or improved patient access. This often entails collapsing or condensing space for other functions with an eye to deploying spaces to be multifunctional. In a multipurpose clinic, for example, it may be possible to convert an existing primary care space into urgent or after-hours care without modifying the facility. A well-defined model will show the strengths and weaknesses of the existing space and highlight existing functions that can be used differently.

Computer simulation modeling can help evaluate design alternatives. Repurposing existing spaces is a tougher design task to tackle than new construction, but computer simulation modeling is extremely valuable for quantifying the benefits of repurposing space versus building new. Examples of this would be testing potential changes in operations during different phases of renovation and testing potential synergies with services and staffing.

To arrive at the best use of existing space to avoid new construction, a model can simulate different configurations to make the best use of capital. In some cases, however, it may turn out that building a new space is the best use of the space and provides a higher rate of return on investment. The modeling allows a planning team to see the potential outcomes and make the best decisions based on those models.

Variables Can Change

Stability of leadership is probably the single strongest predictor of a successful design or redesign project. Unfortunately, leadership is also the factor most likely to change during the life of the project. Administrators who are nearing retirement aren’t eager to make big changes, whereas new staff have their own agendas that may differ from the assumptions of the original planners. Other variables include the availability of capital, changes in the competitive environment and slight shifts of location or orientation. However, simulation models can take all of these identified variables into consideration.

After the model is set up with the baseline conditions, the model can be adapted to changing conditions. If, for example, the target patient volume changes from 60,000 patients to 80,000 patients, a change in one number can quickly reconfigure the model, as opposed to having to redo all the analysis from the beginning. The model can also make adjustments to specific attributes of patients, processes or space as conditions change.

Managing Staff More Efficiently and Effectively

Because humans are unpredictable, accurately modeling staff behavior is a serious challenge for any project. A proposal may have the right number of dollars allocated to staff, but there remains a mismatch in how they are deployed to care for patients. Staff often work in a dysfunctional environment without standard processes to guide their decisions.

For example, modeling can often quantify an overuse of technology, such as when an X-ray is all that the patient needs, but instead a more advance image is ordered because it may provide more detailed information. The hitch is that such precision isn’t always medically necessary.

Some patients require more staff time than others. A young, healthy, active patient requires less treatment than an elderly person with multiple prescriptions who may need assistance with basic self care. The length of time such procedures may take can be highly variable; however, this variation can be accounted for in computer simulation modeling. It’s rare to have many open fulltime positions to fill, so it is especially important to determine through modeling the best alignment of staff with patient time of arrival.

A simple example tells the story. Housekeepers very often work the day shift. The majority of outpatients are seen between the hours of 8 a.m. and 3 p.m. The housekeepers go home, and the emergency room then becomes busy from 3 p.m. to 11 p.m. The challenge is to shift staff around to cover all areas, leaving no gaps in coverage and workload.

A simple example tells the story. Housekeepers very often work the day shift. The majority of outpatients are seen between the hours of 8 a.m. and 3 p.m. The housekeepers go home, and the emergency room then becomes busy from 3 p.m. to 11 p.m. The challenge is to shift staff around to cover all areas, leaving no gaps in coverage and workload.

Staff tasks are based on averages. A standard task that ordinarily takes 10 minutes could require more or less time depending on outside circumstances, such as the age and mobility level of the attendant, his or her experience level and challenges from patients. As the model adjusts for randomness, it uses a triangle distribution to calculate as many potential task lengths before and after the average, and simulates the task length on a random basis.

Optimality requires that staff work at their highest and best level. A nurse should not be primarily tasked with or assigned a simple chore that a less highly trained person can do. A computer simulation model may be designed to plan for a mix of tasks that can be performed by staff in different roles. It can assign a specific staff type to a task or assign multiple staff and prioritize which staff should complete a task: A nurse may be the default role, but if the nurse is not available, a tech can fill in.

A model should be flexible in setting up the configuration and also support a modeling language of preconditions. The model is a kit with parts that allow for different activities, staffing, attributes, variables, task time and shifts. Flexible models provide options for modeling human behavior effectively and for testing any scenario, no matter how unlikely it may be.

Leaner But Not Meaner Management

Most of the work of modeling goes into documenting existing conditions and ideal processes. The difference between the two worlds centers on standardization. The fewer ad hoc workarounds required, the leaner the process. Sometimes the process is derailed by outside influences, such as inefficient workspaces or recalcitrant staff, creating a gap between how work is actually being done and how it should be done. Modeling throws light on these differences. The modeling tools use a lean approach to enhance outcomes with the most efficient process possible by illustrating the effects of reducing or eliminating non-value added work.

Buy In

To achieve leadership buy in, planners must identify goals of the modeling study, communicate them effectively and work toward them in a consistent and intelligent way. They must have a testing plan that will measure the results properly. The “trust me” premise is not as convincing as concrete predictions. When shown that changing process A will result in outcome B, administrators will know exactly what they are getting and will be more likely to buy in.

Modeling Makes Business Sense

Operational modeling takes unnecessary guesswork out of the decision-making process. Unknowns will always pose some risk, but modeling makes it possible to be proactive rather than reactive. Because modeling is so data driven, it’s possible to move quickly, make decisions more effectively and discern cause and effect in a variety of situations. Obviously, huge data stores don’t automatically translate into effective policy, but modeling does broaden the understanding needed to make action-generating decisions.

Michelle Mader, MBA, MHA, is a principal and director of strategy at FreemanWhite. With experience as both a hospital administrator and a health care consultant, Michelle Mader combines a passion for health care with a talent for high-level strategic thinking, empowering clients to navigate complex and fast-paced challenges. She is an effective leader who inspires innovation, creative solutions and the delivery of concrete results.

Delia Caldwell, MBA, is a principal and director of project delivery at FreemanWhite. Delia Caldwell is a lean analyst and project manager, driving process improvement in large-scale projects at both the department and hospital level. She has a particular interest and expertise in using computer simulation modeling and big data analytics to facilitate planning and improvements.